Financial Markets in Phases: Where We’ve Been and What’s Next

December 09, 2022

Perhaps a good way to set reasonable expectations for financial markets is to evaluate them in past and future phases.

Phase One: Global Financial Crisis and Pandemic

During the global financial crisis (GFC), fiscal and monetary policymakers printed and spent money to stimulate the collapsing economy. Debt and deficits exploded along with the U.S. Federal Reserve’s (Fed) balance sheet that served as spending programs’ primary funding mechanism. The process was simple: 1) Congress spends mountains of money, 2) the spending is financed via the U.S. Treasury that issues bonds, 3) the Fed prints money and buys the bonds, and 4) the Fed holds the bonds as assets on its balance sheet. It worked, but the stimulus program known as “quantitative easing” never ended. Cheap money and a stimulated economy were about as good as it could get for financial markets, so up they went.

Years later, the same playbook was used during the COVID pandemic, but new spending, debt issuance, and money printing dwarfed their predecessors during the GFC. It is difficult to exaggerate the profligacy of the spending relative to budgetary history. Financial markets soared again in response to the stimulus, but some worried that the piper will eventually be paid. Enter inflation and a lot of it!

Phase Two: The Battle Against Inflation

Chastened central banks, including the Fed, are now in the process of undoing their inflationary mistakes. Their primary methods are raising short-term interest rates and shrinking their bloated balance sheets. As should be expected in response to such a dramatic reversal, financial markets have entered a deep bear market with almost no asset class left untouched. And unlike during the GFC, stocks and bonds have fallen in tandem, leaving investors with no place to hide from the selloff.

The Fed’s goal with its rate-hiking program is to slow the economy to bring inflation rates down to acceptable levels. That’s where we are now, and it takes us to the next phase that will likely commence in 2023.

Phase Three: Recession or Stagflation

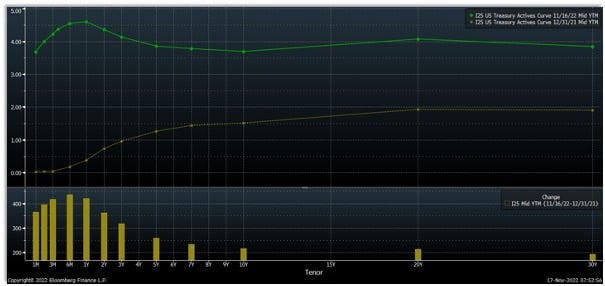

Short-term interest rates have been hiked by the Fed in historic frequency and amount. Starting in March, the fed funds target rate has been incrementally raised from zero to 4 percent, and there is likely more to come before the end of the year. Markets are already discounting a material slowdown in economic growth, as indicated by the chart below showing changes in yields across the U.S. Treasury security maturity spectrum. Obviously, yields have risen a lot for all maturities. But note that the November yield curve at the top of the chart is highly inverted, meaning short-term yields are now higher than their longer counterparts. That is a somewhat reliable indicator of an impending slowdown. Yes, one is coming, but how slow it gets is yet to be determined.

U.S. Treasury Yield Curves: December 31, 2021 and November 16, 2022 (Source: Bloomberg)

With a slowdown very likely next year, investors must set expectations that are reasonable under the circumstances lest they become ambushed by unexpected events. In our view, two scenarios are possible: 1) recession, and 2) stagflation.

As indicated by the shape of the yield curve, a recession is probably already discounted in markets. Indeed, one of the best things the market has going for it is how much damage it has already experienced. A recession would cause market-supporting corporate earnings to fall, but interest rates would stabilize because inflation would subside due to decreased demand. Markets could rally based on expectations for an impending recovery and stable or falling interest rates. Not bad.

The alternative to a recession is stagflation. Here corporate earnings fall due to a modest slowdown in the economy, but interest rates remain high because inflation is still a persistent problem. Earnings down and rates up is an ugly environment for financial markets, so a rally normally experienced during a recession likely wouldn’t happen. Pain experienced in 2022 drags on into 2023.

We believe a recession is likely, and we believe the ugliness of stagflation, while certainly a possibility, is unlikely to occur. But even the better option (recession) comes with a cost. The unemployment rate must rise by a meaningful amount if inflation rates are to come down. Otherwise, strong labor markets would keep the Fed and other central banks on their current path of aggressive rate hikes. Again, current pain extends well into next year.

Sadly, the ghoulish hope for rising unemployment is, in the aggregate, best for the economy and financial markets in the near term. So, let’s hope for an inflation-killing recession. Gosh, did we actually say that?!

The views presented here are the author’s alone and not necessarily representative of opinions held by CUNA Mutual Group or any affiliated entity.

Written by: Scott Knapp, CFA

Scott D. Knapp is the Chief Market Strategist with Cuna Mutual Group. Scott is responsible for investment philosophy development and program implementation for Cuna Mutual Group’s Institutional Retirement Programs. He regularly speaks at economic and investment forums across the country. Connect with Scott on LinkedIn.

CMRS-5343190.1-1222-0125